Three thousand years ago, Egyptian physicians developed a new procedure for treating illness – bloodletting. We will never know how many patients were killed by this treatment, but King Charles II and President George Washington were almost certainly two of them. It seems ridiculous today, but the practice persisted for 2,800 years. Only in 1828 did Dr. Pierre Charles Alexandre Louis prove the treatment was ineffective, yet its use persisted for much of the 19th century. 100 years from now, I’m sure many common procedures we rely on in medical treatment will be considered ridiculous as well.

Raising interest rates to control inflation has been the primary strategy of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors Federal Open Markets Committee (FOMC). This approach was essential to curtailing extreme inflation in the late 1970s and early 1980s, despite its high cost in jobs and near-term economic growth. It did cure inflation, though at the cost of a severe recession that cost millions of people their jobs. The Fed’s response to our current battle with inflation has made sense in a historical context, but how is it working today?

Raising interest rates hasn’t succeeded in cutting inflation

The surge in inflation in 2021 and 2022 was driven by a wide range of factors. Pandemic related supply chain shortages were significant. Oil and food costs were also impacted by the pandemic, and are always volatile. These factors caused inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to rise to 9.1% last June. Today, the CPI is down to 5%, which may seem like a major improvement, but is it? Core CPI, which excludes highly volatile energy and food prices, has remained stuck above 5% since the end of 2021 despite FOMC rate increases totaling 4.75 points. Last week, it was reported at 5.6%, having risen in March.

Raising rates has had a negligible impact on reducing inflation in part because it has contributed to an increase in the cost of shelter. This month the Department of Labor said shelter is “by far the largest contributor to the monthly all items increase,” noting that this “more than offset a decline in the energy index, which decreased 3.5 percent over the month as all major energy component indexes declined.” With the announcement that OPEC is cutting production, we can also expect fuel costs to be much higher in the months ahead. Based on the evidence, raising rates above their current level is not likely to succeed in reducing inflation. If the FOMC continues to increase rates, the cure could kill the patient and risk triggering a severe recession combined with inflation – stagflation.

Until now, I have been a strong supporter of the Fed’s aggressive efforts to control inflation through increased interest rates, despite the disproportionate impact on housing, because inflation disproportionately impacts lower-income people. Nearly two years ago, I warned about inflation’s extremely regressive impact, noting “purchases of consumer goods are a much smaller part of high-income budgets.” Today, I believe the Fed must stop raising rates and let the economy absorb the previous rate increases while we focus on increasing housing supply to address skyrocketing shelter costs.

Higher rates are feeding housing inflation

Higher rates have virtually eliminated the refinance and move-up markets. This change has had a dramatic impact on the balance sheets of independent mortgage banks. At the same time, banks have struggled with balance sheets loaded with years of low-rate mortgages and other investments that have ballooned their unrealized losses, leaving them vulnerable to large deposit withdrawals that can turn into a bank run in hours. This leaves the first-time homebuyer market as the remaining pillar of the residential mortgage market. It’s also the heart of the remaining market for single-family home construction. Yet high rates and insufficient supply are crushing this market, feeding higher shelter costs.

Housing is a continuum. Fewer homebuyers means more renters and higher rents, as we have also seen. As rents rise, so does homelessness. While rents are flattening out, we will continue to see increases in homelessness due to recession and a growing group of senior citizens with limited and fixed retirement incomes, little savings, and rising costs.

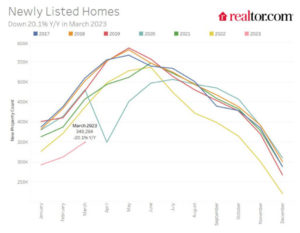

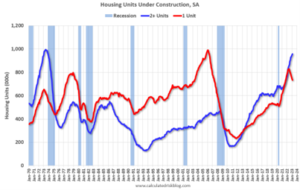

As Bill McBride’s Calculated Risk blog reported this week, there are 734,000 single-family units under construction, seasonally adjusted. “This is 81,000 below the recent peak in April and May. Single-family units under construction have peaked since single-family starts are now declining.” The rental market, however, continues to be strong, and construction of multi-family units continues to increase. “Currently there are 957,000 multi-family units under construction,” McBride said. “This is the highest level since November 1973!”

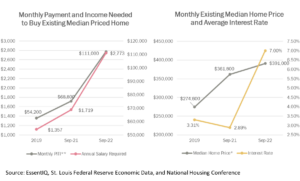

For first-time homebuyers, the median home price before the pandemic was $274,000. Today, it is nearly $400,000. Interest rates before the pandemic were 3.31% and fell to 2.89% in September 2021. This fueled the final refinancing boom and pumped billions of dollars into the economy. It also helped fuel the rise in home prices. As a result, the monthly payment on a median-priced home increased from $1,257 to $2,773 in three years, while the income needed to afford that same home

For first-time homebuyers, the median home price before the pandemic was $274,000. Today, it is nearly $400,000. Interest rates before the pandemic were 3.31% and fell to 2.89% in September 2021. This fueled the final refinancing boom and pumped billions of dollars into the economy. It also helped fuel the rise in home prices. As a result, the monthly payment on a median-priced home increased from $1,257 to $2,773 in three years, while the income needed to afford that same home

more than doubled from $54,000 to $111,000. Until incomes catch up with housing inflation, either through higher wages, which is inflationary, or lower housing costs through increased supply, shelter will continue to fuel core inflation.

Higher rates won’t offset $11 trillion in stimulus

It’s time for the Fed to stop raising rates and let the economy absorb the impact of the current rate regime. It’s also time for federal policymakers outside the Fed to recognize fighting inflation is a job we all share. During the first two years of the pandemic, the Fed pumped $4.5 trillion dollars into the economy through quantitative easing, an experiment never before attempted. Some of this stimulus was essential to getting the country through the pandemic, but there is no question it also contributed to a dramatic increase in inflation. Congress, in the meantime, has pumped another $5 trillion dollars in the economy through multiple emergency spending bills, including $814 million in direct cash payments, as well as an additional $2.3 trillion in tax cuts just before the pandemic became apparent. Much of this spending passed with bipartisan support. We got into this together and that’s how we will have to get out of it.

Enact meaningful housing supply policies

Federal support for increasing affordable housing supply, the largest driver of Core CPI “by far,” has failed to make it into any of those bills. In fact, the 2020 tax bill diminished the value of housing tax credits, while none of the Biden stimulus bills included the Neighborhood Homes Investment Act and the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act. If enacted, these two bipartisan bills would create 2.5 million affordable housing units over the next 10 years.

In his annual letter to shareholders, JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon warned that when responding to the SVB failure, “it is extremely important that we avoid knee-jerk, whack-a-mole or politically motivated responses that often result in achieving the opposite of what people intended.” This is more important now than ever. We are in the early days of a long period of significant interest rate risk. Congress’s failure to appropriately address this risk in the 1970s fueled the second Savings and Loan crisis in the 1980s. We don’t need more regulation, or less regulation, we need better regulation.

Two housing-specific examples are the HOME Investment Partnerships Program and the Housing Choice Voucher program. NHC has been and will continue to work closely with the Biden administration to make these programs easier to use. In a political and economic environment where major spending on domestic discretionary programs is highly unlikely, we need to make sure every taxpayer dollar goes further. We also need to thoroughly review regulations on the servicing of mortgages to ensure they are not contributing to eliminating the profitability of smaller mortgages. As Axios recently reported, too many lenders can’t afford to make the most affordable mortgages.

We know what we must do

If we fail to address inflation, the likelihood of a prolonged period of stagflation will continue to increase. Stagflation is the political equivalent of two hurricanes combining to create a perfect storm. It will take everything we have to fight it. The good news is we know what we must do. Increasing housing supply is the key to success.