This month’s devastating pair of catastrophic hurricanes have brought home the skyrocketing cost of climate change, in lives, property, and economic growth. And before the U.S. government distributes one penny of newly appropriated emergency assistance, homeowners, homebuilders, and those in need of affordable housing, will pay billions in exponentially higher insurance costs.

Sadly, the politicization of climate change continues unabated. Earlier this year, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis (R-Fla.) signed a bill deleting the phrase ‘climate’ eight times from existing legislation. What a waste of time and energy. Yet too many climate activists remain tone deaf to the devastating impact moving away from fossil fuels will have on millions of middle class workers. If you’re a 50 year old high school educated worker in the coal, gas, or oil industry and you lose your job, you are likely never going to work again. The likelihood that someone else may get a new job won’t feed their family.

It’s not just a partisan divide. Failure to reform the National Flood Insurance Program has been driven by geography more than party, though the biblical scale destruction of Ashville and so many smaller towns in North Carolina, located 2,220 feet above sea level may pry these lines apart.

I also wish we would stop talking about saving the planet. The planet Earth is going to be just fine. It is incredibly resilient, having survived five mass extinctions over the past 444 million years. We humans, however, will not be fine at all. Tragically, if you lived in the path of Hurricane Helene, you know what that looks like.

Any tangible, impactful, and achievable solutions will require us to start over because what we have done to date has failed. Blaming others for our failure is an inconvenient untruth. The facts speak for themselves. As a nation, we desperately need to find a new consensus that effectively crosses the vast political divide in which we currently operate. The devastating price being paid by so many “red” communities may be an opportunity, but only if we are able to truly empathize, listen, and collaborate.

So let’s start with the poster child of failed programs, the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). A 2021 paper in Princeton University’s Journal of Public & International Affairs stated it best.

“The NFIP has failed significantly in at least two core areas: reducing development in floodplains and maintaining solvency. First, with regard to development, many claim that the NFIP’s subsidized insurance structure actually incentivizes risk-taking and has led to further flood-prone development (Strother 2018). Second, the program is in debt and sees low participation—despite insurance premiums being its intended primary source of revenue. Other common criticisms of the NFIP include: it does not regularly update flood maps with modern scientific information; it also does not take into account future risk projections, but instead utilizes only historical flooding data; it causes confusion by relying on the false boundary of the 100-year floodplain, and largely ignores flood risk outside of these areas; it does not include much by way of transparency requirements, so buyers and renters are often in the dark about a property’s risk; it rarely regulates participating municipalities’ floodplain ordinances; it is overly reliant within SFHAs on subsidized and grandfathered premiums, which do not represent actuarially accurate risk rates; and it neglects its buyout offerings while incentivizing rebuilding in high-risk areas.”

In 2014, Congress passed a major reform of the NFIP, cosponsored by Representatives Maxine Waters (D-Calif.) and Judy Biggert (R-Ill.). But major elements of the bill were repealed a year later due to opposition by those whose rates went up because of their substantially higher risk. That’s right. We passed a major NFIP reform and then repealed it a year later because it did what it was intended to do. Since then, we’ve just bailed water out of a boat with a hole in it.

In September 2017, FEMA reached its borrowing limit of $30.435 billion and the following year, Congress cancelled $16 billion of NFIP debt to make it possible for the program to pay claims for Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria. FEMA borrowed another $6.1 billion on November 9, 2017, to fund estimated 2017 losses, including those incurred by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria, increasing the debt to $20.525 billion. The NFIP has not borrowed from Treasury since 2017. However, Congress has enacted 31 short-term NFIP reauthorizations over the past seven years. The NFIP is currently authorized until December 20, 2024, when any reasonable person can expect Congress to do another short-term reauthorization. Given the devastation of this hurricane season, another bailout without reform is likely.

That’s such a shame because the cost of failure is so high and increasing exponentially. CoreLogic estimates that the insured losses from Helene will be $6 billion to $11 billion. But the uninsured flood losses are estimated to be $20 billion to $30 billion.

According to the Washington Post, the FEMA flood maps, used to assess flood risk, found that “just 2 percent of properties in the mountainous counties of western North Carolina fall inside areas marked as having a special risk of flooding.” The Post’s analysis of data from First Street, a climate modeling group data, found that the number of properties at risk could be seven times higher than what FEMA flood maps indicate. FEMA flood maps determine whether or not homebuyers must have flood insurance to get a government-backed mortgage.

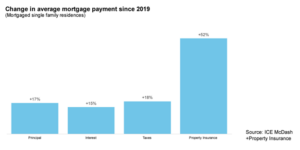

Hurricane Helene may have caused a quarter of a trillion dollars of damage, including $47 billion of losses to homeowners. In Florida, where flood insurance is more common, the price and availability of insurance is likely to skyrocket in the wake of Hurricane Milton. The average property insurance payment in Jacksonville, Fla., has already risen by 86% since 2019, according to ICE’s Mortgage Monitor — compared to a 52% rise nationwide, AXIOS reported. And commercial insurance rates are even worse.

Homeowners are already paying the price. According to an ICE Mortgage Monitor Report published shortly before the recent hurricanes, “the average mortgage payment (principal, interest, taxes, and insurance) among existing homeowners climbed to a record $2,070 in August, up $140 per month (+7.2%) from the same time last year and $399 per month (+23.9%) from the start of the pandemic.” Rising insurance premiums were the largest factor in the increase, rising 52% since 2019.

“In New Orleans, as well as Florida markets such as Deltona, Jacksonville and Cape Coral, monthly property insurance payments increased more than 80%. Premiums also surged in areas with rising home values, including Utah; Boise, Idaho; and Midwest/Eastern Slope markets like Omaha, Denver and Colorado Springs, which have faced increased risks from tornados and hail damage,” ICE reported.

That’s right. Boise, Idaho and Omaha, Nebraska.

I often say that housing is a continuum. We are all in this together. An article in the New York Times this summer reported on a nonprofit homeless services provider and housing developer in California, Father Joe’s Villages, that saw its insurance premiums quadruple this year to $4.4 million, combined with a sharp increase in their deductibles. Other affordable housing providers, faced with similar increases, are cancelling projects to build new affordable housing, and selling some affordable properties to cover insurance costs on others, according to several NHC members.

So now what?

NHC’s members are hard at work on these issues. For example, the Housing Partnership Network’s Insurance Exchange (HPIEx) covers over 85,000 units of affordable housing valued at more than $11 billion for 23 Housing Partnership member organizations. HPIEx is the first property and casualty reinsurance company created, owned and operated by nonprofit housing developers. It offers members property, liability, and workers compensation coverage, customized loss control services, and stable premiums.

NHC joined a group of 24 major housing organizations spanning the political spectrum and sent members of Congress and the Biden administration a letter on a wide range of bipartisan policies to address the causes of rising insurance premiums across the nation’s housing market. The coalition, led by the National Multifamily Housing Council, focused in particular on the significant negative impacts premium increases have had on all stakeholders, including, but not limited to, single-family, multifamily, and affordable housing developers, lenders, investors, owners, and the nation’s renters. It’s a start.

This note is the first in a series of essays over the coming year that explores how NHC’s politically and sectorally diverse members can work together to mitigate the impact of climate change. We will begin with where we are now, and work together toward where we need to be. That starts with you. Please reach out to me at davidmdworkin@nhc.org and NHC’s Director of Research Brittany Webb at Bwebb@nhc.org with your thoughts.