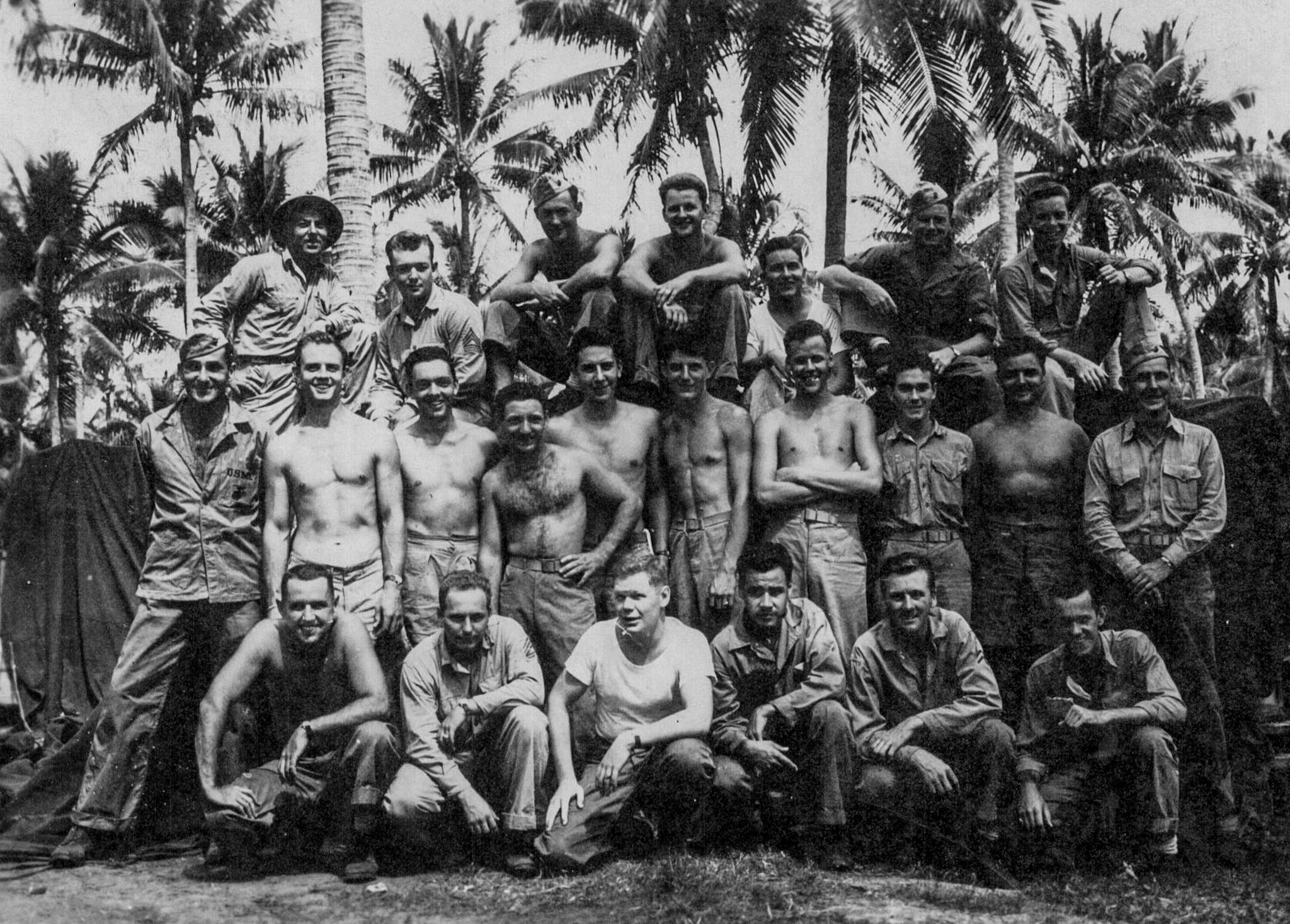

My father Edward Dworkin spent his teenage years working in the junkyard his father ran on a rented lot in Detroit during the Great Depression. His father spoke two languages fluently, as well as the broken English I struggled to understand. When he turned 18, my father enlisted in the Marines and traveled 8,000 miles from his home in Detroit to serve his country.

The sacrifice of that Greatest Generation is legendary, captured in countless movies and books. Sixteen million Americans served in World War II – a quarter of the U.S. population. More than 405,000 never made it home. Those who survived the Second World War were rewarded for their service with the G.I. Bill of Rights, which offered the opportunity of a college education and subsidized homeownership. As a result, my father was the first person in his family to go to college and own his own home. He wasn’t alone. The U.S. homeownership rate increased from 41.2% to 66.4% between 1940 and 1960, creating wealth for millions for the first time.

However, not everyone benefited. Over a million people of color, most of them Black, also served in World War II. Nearly all of them were excluded from receiving benefits under the G.I. Bill because the same federal government that created the G.I. Bill of Rights also excluded people of color from receiving mortgages with VA and FHA loans. Between 1940 and 1960, the gap between Black and White homeownership increased by over five points from 21.9 to 27.3. Today, that gap is more than 30 points.

It’s easy to think of this injustice as ancient history. With the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968, discrimination in housing and education has been illegal. So why has the gap increased rather than shrunk? There are a lot of reasons, but one of the most impactful is the tremendous influence of multigenerational wealth, created by multigenerational homeownership and attendance at college – without student loan debt – that grew out of the G.I. Bill of Rights.

Multigenerational homeownership creates three significant advantages that can make the difference between building multigenerational wealth or remaining in the lowest rung of the middle class.

The first reason is the most intangible – the presumption of homeownership in families that live in their own home. No one doubted my brother and I would become homeowners. Clearly, this is not the case in families where generations of households were denied the right or ability to own their own home.

Second, my parents were available to encourage me and advise me at every step of the process. They explained that I could buy a home with a 5% downpayment, the relationship between equity and debt, and the importance of planning for future maintenance. They discouraged me from making an offer on a home they saw, warning me it had cheap windows and a poorly constructed banister, and likely had other issues we could not see. I was disappointed and felt a little foolish until we found a home that was better, and I understood the difference.

This advice is essential to demystify a process that by its very nature is judgmental and intimidating. Twenty years ago, Fannie Mae did extensive research on the attitudes of consumers across the income and racial spectrum. By far the most interesting fact we learned was that Black first-time homebuyers who were approved for a mortgage believed the system was rigged against them because of their race significantly more than Black first-time homebuyers who were rejected. It’s hard to believe, but what we realized was those rejected early tended to blame themselves for believing homeownership was possible for them. Those who were approved were more likely to be triggered throughout the process

The third advantage is palpable. My wife and I both had jobs and worked hard to improve our credit and save for a home. But we also participated in what I call the Daddy Downpayment Program. My parents gave us $10,000 to help with our downpayment and closing costs. We wouldn’t have been able to afford our first home without it. It was made possible by the wealth they built over a generation, aided by government programs and subsidies not everyone received.

I’m grateful for the help I received, and I worked hard for what I have. But let’s be clear. Just because I was born on second base, doesn’t mean I get to brag about hitting a double. Most of the children of Black World War II veterans did not have parents who went to college and became homeowners with the G.I. Bill of Rights because they were denied these benefits, in spite of the U.S. Bill of Rights. For them, there was no feeling of entitlement to homeownership, no reassuring advice from parents, and no Daddy Downpayment Program.

The good news is we still have an opportunity to right this wrong. We aren’t saying anyone should get anything they haven’t earned. Quite the contrary. We need to do everything we can to ensure everyone can benefit from the same opportunities some of us got, and others were denied.