by Robert Hickey, Center for Housing Policy

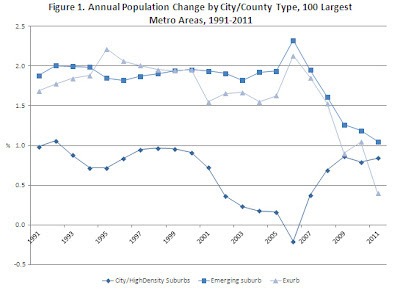

The Brookings Institution recently profiled an important new trend: cities and high-density inner suburbs are now growing at a faster rate than the nation’s exurbs—those communities at the region’s edge whose boom once seemed unstoppable. This interrupts a pattern dating back more than two decades during which housing development consistently favored outer suburbs over urban areas. The findings provide new evidence of a shift toward urban living that has important implications for the affordability of our compact towns and cities.

The graph from the Brookings Institution below will not come as a complete surprise to many. Previous posts here have noted the surge in rental demand in cities, the declining appeal of remote suburbs that require extensive driving (especially as gas prices rise) and the shifting demographics that are fueling demand for closer-in, walkable town centers and cities. (See also recent research from RCLCO).

But for study author William Frey, this latest evidence “raises the prospect that we may be reaching a ‘new normal’ about where people decide to locate.”

|

| Source: William Frey, Brookings Institution |

Short-term forces may help explain the decline in housing starts at the periphery, as has been suggested elsewhere. But rising gas prices and our increasing numbers of smaller households and older adults would suggest that the decline in far-flung suburbs is more than just a short-term market-correction.

All this points to a growing need to start thinking now about how to get ahead of this housing curve. The latest findings from Brookings should add urgency to efforts to ensure ongoing affordability for a diversity of employees and households in our urban settings.

As the Washington, D.C., region and other metropolitan areas have discovered, new housing construction does not necessarily mean more affordable choices for lower-wage workers, not does it protect existing residents from the displacing forces of gentrification. For example, in Washington, D.C., the supply of apartments for lower-income households fell by more than one-third between 2000 and 2007 (and the supply of moderately priced for-sale homes shrunk even more), even as the city added more than 10,000 new homes, according to research by the DC Fiscal Policy Institute.

Given the high costs of development in many urban areas, new rentals are being priced at the upper end of market, and new condominiums (while less than the price of single family homes) are still well out of reach for lower-income residents. Absent policies that reduce overall development costs, and set affordability expectations for new development – especially where public actions create new value – this pattern will continue, and growing demand for city and town-center locations will exacerbate affordability problems in those locations.

Fortunately, there are many tools available to help city policymakers balance urban reinvestment with affordability. This includes zoning reforms that include value capture mechanisms, inclusionary housing and policies that preserve the affordability of for-sale and rental properties in areas undergoing major transit investments. A great place to learn about these and other tools is the Center for Housing Policy’s ever-growing Sustainable and Equitable Development toolkit.