By David M. Dworkin

With COVID-19 cases surging in new states and the expiration of the CARES Act unemployment benefits just three weeks away, many renters’ housing may be in jeopardy. Roughly 30 million of the country’s 100 million renters have little to no confidence in their ability to pay their next month’s rent due to the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a LendingTree analysis of Census Bureau data.

Some of these renters may not get unemployment insurance or may have experienced significant delays in getting their unemployment insurance approved. Others have lost a considerable portion of their income. They were already stressed before the pandemic, so it doesn’t take much to push them over the edge.

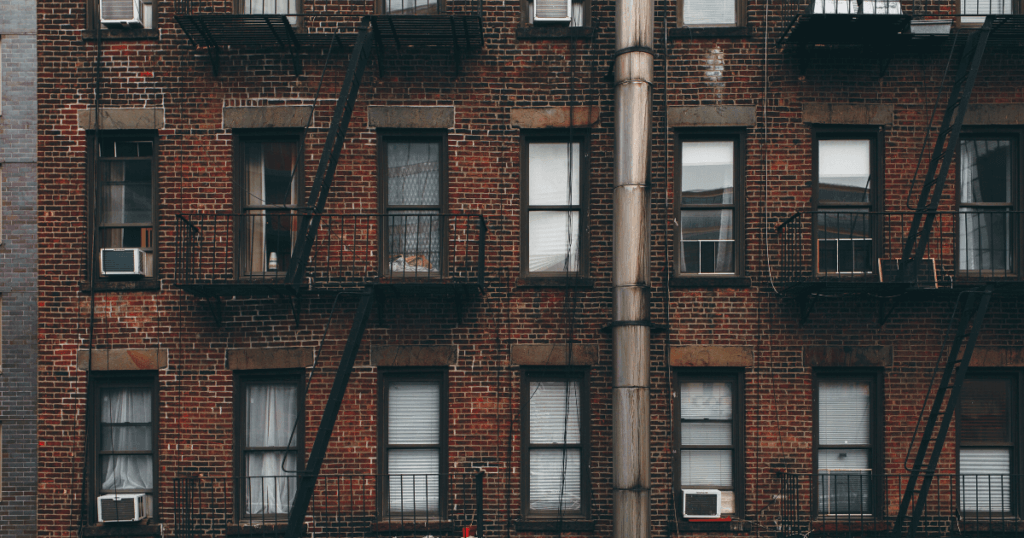

At the same time, eviction moratoriums put into effect at the onset of the pandemic are expiring, creating an eviction cliff that could be devastating to families and neighborhoods throughout the country. These eviction moratoriums were only a temporary measure – a band aid on the real problem of millions of financially vulnerable renter households. What’s more, eviction moratoriums do nothing to help landlords pay their own bills. I don’t think we want to see hedge funds own all of our apartment buildings, but if we don’t help the tens of thousands of small businesspeople who own rental units, that’s where we’re going to wind up.

Several markets are particularly high risk for widespread evictions right now. These include cities like Birmingham, Kansas City and New Orleans, which are in states with poor renter protections. Other cities, like Las Vegas, Orlando and Atlantic City, have been disproportionately hurt by layoffs of vulnerable low wage workers, and several, like Oklahoma City, Memphis and Detroit, have high concentrations of single family detached rentals that aren’t followed by any of the rent payment trackers we watch.

This growing crisis is ignored at great risk of tragedy. Without comprehensive rental assistance like the $100 billion plan included in the HEROES Act, many communities will find themselves in the position of having local police and sheriff’s deputies enforcing eviction orders in low-income neighborhoods after weeks of protests against police brutality and racial injustice.

Eviction is a very public experience that impacts the entire community. Your belongings are dumped on the street while your children and neighbors watch. Given the high degree of tension we are already experiencing, I don’t think that’s a dynamic we want to test.

Regardless of when the moratoriums expire, renters cannot possibly catch up on all of their missed rent payments during the pandemic. This is a once-in-a-100-year pandemic and it’s reasonable to expect the government to cover most of the unpaid rent. It’s no different than the government helping rebuild a city after a major hurricane or flood. That’s why we must pass comprehensive federal rental assistance. Otherwise, we are telling tenants to become homeless and landlords to eat the loss and sell out to the highest bidder. Not even the most conservative budget hawk believes that a massive increase in homelessness in the midst of a global pandemic is a good idea. Nor is having millions of units of rental housing owned by hedge funds.

Congress acted remarkably quickly and with unprecedented bipartisan accord in the first weeks of the crisis. Since then, they have retreated to traditional battle lines, which is understandable but very dangerous on many levels. We need to get back on the same page.

The House has passed significant legislation to address this next phase of the crisis. I understand that many Republican senators believe that the House plan may be too expensive. The answer to that is easy. Negotiate. Let’s get together and find some middle ground. But don’t delay. We don’t want to be Wily E. Coyote flapping our arms after we’ve driven off of the cliff. It will be too late.

David Dworkin is president and CEO of the National Housing Conference