Adi Talwar

One of Cypress Hills Local Development Corporation’s senior housing facilities, on Jamaica Avenue in Brooklyn. Thanks to CRA, Cypress Hills LDC has been able to secure loans to build deeply affordable housing that, on paper, would have been a tough sell to underwriters.Philip Wischerth has the dubious distinction of being the city’s top evictor. Wischerth collects rent from tenants in 12,789 apartments across all five boroughs, most notably Lefrak City. In 2018, he used city marshals and court proceedings to evict 189 households, the most of any landlord in the city. That’s one eviction in every 67 apartments—three times the citywide average.

Though Wischerth is the record-holder in terms of sheer numbers, another landlord, Ved Parkash, had a staggering rate of eviction in 2018: one eviction for every 24 units of the 4,482 residential units he owned. That’s an eviction rate of over 4 percent—in the same ballpark as some of the neighborhoods hardest hit by eviction in the entire city, like Bedford Park in the Bronx.

Wischerth and Parkash are just two of the landlords with the most evictions in the city, landing them on the NYC Worst Evictors List compiled by tenant advocates Right to Council NYC Coalition and Just Fix NYC. But despite infamous reputations, they had no problem securing loans from major banks.

Wischerth received loans from Chase, Wells Fargo, M&T Bank and Capital One, according to ACRIS records. The same records indicate that Parkash is funded by Signature Bank, New York Community Bank, Peapack Gladstone and Capital One.

While tenant churn, dilapidated buildings, reams of lawsuits and bad publicity might seem like signs of a problematic investment, these landlords (and others like them) have the support of major financial institutions.

Under a federal anti-redlining financial regulation, the Community Reinvestment Act, banks that lend to even the shadiest landlords may even receive credit for serving the low-income communities that they are helping those landlords to exploit.

The CRA, a crucial but flawed tool intended to give communities leverage over banks, is up for reform — and though community advocates have long advocated for substantive changes to the law, they are currently worried about conservative moves to hobble it.

A reaction to redlining

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) was passed in 1977 as a form of redress for redlining, a practice that began following the Great Migration in which banks systematically denied home loans and mortgages to black homeowners. It is a federal law that asserts banks have an obligation to invest in low-income neighborhoods in the area they operate in.

It calls for banks to be evaluated every two to five years on their compliance. The ratings are posted publicly. Virtually all banks pass their exams (0.3 percent of banks have been judged to be in “substantial noncompliance” with the legislation since 1990), which advocates see as a sign of grade inflation.

While the consequences of redlining persist to this day, the practice does not endure in the exact same form: some of the areas left for dead in the 60s and 70s are now ground zero for gentrification. As the economic situation shifts from redlining, which is a pattern of deliberate underinvestment, to speculative investment pouring into formerly redlined neighborhoods, advocates say the CRA has sometimes rewarded investments that fund displacement because regulators aren’t empowered to distinguish between predatory investments and constructive ones.

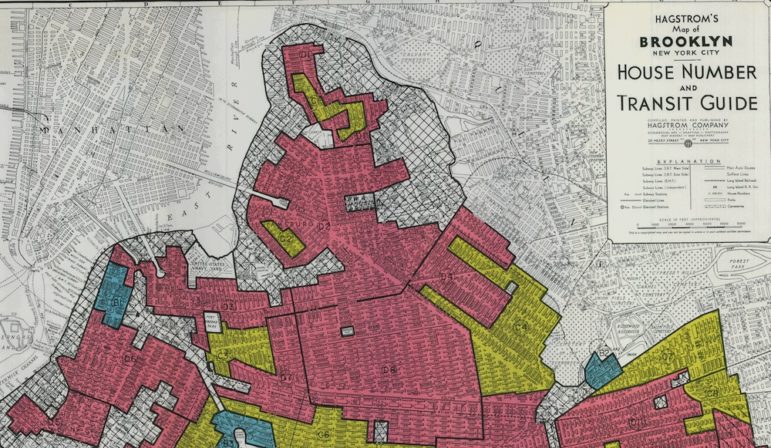

HOLC

A redlining map of Brooklyn.“The folks leading the charge at the time fundamentally believed they could get the banks to work for them the way they worked for other non redlined communities,” explains Gregory Jost, a community organizer for the South Bronx nonprofit developer Banana Kelly, who is writing a book on the history of redlining in the Bronx.

But over the years, the legislation has become bureaucratic, overcomplicated, and disconnected from the communities in which anti-redlining organizing took place, Jost argues: “The people that actually were around for the CRA’s passage are for the most part no longer with us and over the past 45 years it’s become disconnected from the grassroots.”

The CRA is a fairly simple law, but its enforcement metrics are complex and that has resulted in it becoming restricted to the province of experts. It’s arguably this technocratization that has allowed for toothless enforcement.

“We have to push back against unnecessary complication of matters. The metrics don’t have to be super complicated,” Jost said.

“That’s always been a tool of people in power to make things wonkier than they actually need to be: Make it confusing to keep it out of the hands of the people.”

To be sure, the CRA does divert some of the banks’ wealth towards financial commitments that wouldn’t otherwise happen. Some of the investments that count toward CRA compliance are investments in affordable housing developments—a key component of affordable housing policy in New York City, which relies heavily on public-private partnerships.

According to the city Department of Housing Preservation and Development, all the public money the agency puts into new affordable projects is matched approximately four times over by infusions of private capital, which are incentivized by the CRA. (Mayor Bill de Blasio’s affordable housing plan, announced in 2014, forecasted a contribution of $30 billion of private money to promise a total investment of $41 billion in affordable housing.)

Where the CRA has historically had some teeth is at the level of community banks, according to Michelle Neugebauer, a staffer at Cypress Hills Local Development Corporation since 1984.

“When I first started here,” Neugebauer said, “there were banks that did not provide a single mortgage loan. Not one.” Among those banks were City National and Anchor Savings Bank. Cypress Hills LDC was able to lobby a local representative who sat on the State Senate Banking Committee to pressure these state-chartered banks to respect their CRA obligations.

Cypress Hills LDC has been able to secure loans to build deeply affordable housing that, on paper, would have been a tough sell to underwriters, Neugebauer said. “Everyone’s looking at your balance sheet. We’ve gotten multi-million-dollar deals even though, on the strength of our balance sheet, it would not go through because all of our profits go back into organizing.”

While the CRA has secured crucial funding for community development projects, its power is most easily wielded against smaller community banks—the kind that can be swayed through local political mechanisms, like, say, appealing to a local State Senator who might sit on the state legislature’s finance committee. But in recent years, wave of mergers and acquisitions has led to fewer state-chartered banks, leaving the landscape dominated by megabanks that are in effect too powerful to regulate.

Still, the legislation remains an important achievement, Neugebauer said.

“It’s one of the few tools we have to get positive, affirmative investment in our communities. People fought really hard for it.”

Problems with enforcement

The “big three” federal financial regulators are in charge of CRA compliance: the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and the Federal Reserve. Banks are evaluated in each state they operate in by one of the three regulators in conjunction with the state regulator. Each federal and state agency has its own distinctive approach towards CRA compliance.

In New York state, regulators are to evaluate banks’ lending patterns according to their impact on communities’ quality and affordability of housing. If a landlord allows their properties to fall into disrepair or contributes to a decrease in affordable housing—for example, if a landlord’s buildings contain 800 fewer rent-stabilized now than ten years ago, which happened under Donald Hastings, a landlord working for A&E Management—state financial regulators have the power to sanction the banks that fund them. But that does not appear to have happened.

Five years ago, The New York State Department of Financial Services (DFS) in 2013 set out what it called Slumlord Prevention Guidelines. The agency, which conducts state CRA exams along with the FDIC, said in a press release that not all the loans a bank made in a low to moderate income community would count toward CRA compliance.

If the underwriting on a loan is premised on jacking up the rent on rent-stabilized units in the future to provide a return on investment, or if the building being underwritten has numerous housing code violations, DFS said it would punish the bank.

“Loans that undermine affordable housing or neighborhood conditions, facilitate substandard living conditions, or are underwritten in an unsound manner will not be eligible for CRA credit,” according to DFS guidelines. “For example, loans to borrowers with a high number of housing code violations or loans that are too highly leveraged (too much debt financing) will not receive CRA credit.”

That means the regulator should “knock out” the offending loan from consideration rather than taking that loan into consideration and possibly lowering a bank’s grade. DFS confirmed this is how the agency proceeds but would not comment on whether the slumlord prevention guidelines had resulted in any banks actually being downgraded on the CRA ratings. Some of the smaller local banks named and shamed by the tenant advocates and then by DFS—namely Signature Bank and New York Community Bank—announced they were adopting best practices for multifamily lending and holding themselves to a higher standard than regulators required, a move advocates applauded.

The problem with “knocking out” loans deemed bad is that changing urban economics have lessened the bite of this sanction. When redlining was at its peak, removing a loan from CRA consideration would have been a harsher measure. By definition, banks were reluctant to lend in redlined neighborhoods, so to “knock out” a loan when those loans are few and far between might have at least been a serious inconvenience. But today, with investment pouring into formerly redlined, “up-and-coming” neighborhoods, banks now have plenty of other loans to submit for consideration instead.

So what incentive do they have to change their lending practices? All of the banks that lent to the city’s worst landlords passed their state CRA exams with a grade of “satisfactory” or “outstanding,” meaning financial regulators judge that these banks are doing a good job at contributing to low-income communities.

In fact, since 1990—which is as far back as the data available from the federal regulators goes—only 238 banks in the entire United States have received a CRA rating of “substantial noncompliance” out of 75,926 exams. That’s 0.3 percent. A further 2,515 received a rating of “needs to improve.” The other 95.78 percent received outstanding or satisfactory ratings.

Even in the highly unlikely event that a bank receives a failing rating, it doesn’t necessarily come with real consequences, advocates say. Since 1990, all CRA ratings are posted publicly online, which means reputational consequences for a bad rating, if a bank cares about that sort of thing. (Which, to be clear, some of them do.) But other consequences are lacking.

If a bank is downgraded from Satisfactory to Needs to Improve, the enforcement consequences aren’t immediate: a bad CRA rating can result in regulators not approving a merger or an acquisition. This isn’t enough, according to Gregory Jost, the organizer at Banana Kelly. They offer carrots to reward banks for CRA commitments—getting regulatory approval for things like mergers and acquisitions depend on a bank’s CRA rating—but there are few actually punitive sticks to punish bad actors.

“There aren’t enough sticks, and the banks don’t want there to be sticks,” Jost said.

Another flaw is actually baked into the original text of the CRA: even though it was fought for as a remedy to a racist practice, the CRA does not take race into account. It instead incentivizes banks to invest not specifically in black communities or communities of color, but in low- and moderate- income neighborhoods.

Furthermore, it does not distinguish between lending to a rich person who wants a home loan to buy a house in a poor neighborhood or to a poor person who wants to buy in that same neighborhood: both loans would be equally rewarded in a bank’s CRA exam.

That’s because CRA was a product of its historical context, and it plays something of a different role today. The CRA simply rewards banks for making a sufficient amount of loans in poor and working-class neighborhoods, because at the time when it was passed these neighborhoods were starved for investment.

But today, at least in New York City, previously underinvested neighborhoods are dealing with a very different problem: overinvestment driving up real estate prices and displacing low-income people. In rewarding banks for making a high volume of loans in poor areas, the CRA can end up validating investments that spur gentrification—which displaces the exact communities the CRA is supposed to benefit.

For example, when Cypress Hills was rezoned as part of the East New York rezoning—Bill de Blasio’s first foray into such a reform—this led to speculative investment, according to Neugebauer, from Cypress Hills LDC. Long-standing homeowners (the neighborhood has many first-generation homeowners) were targeted. House-flipping became endemic. Even as these changes continue, banks will not cease to get credit for lending in Cypress Hills because it remains a low-income census tract—even if they give a home loan to a wealthier home buyer looking to the neighborhood to snag a deal.

“Banks shouldn’t get CRA credit for market-rate housing or to high- and middle-income people,” Neugebauer said.

The CRA was neither designed with gentrification in mind nor updated to counteract it, which is why, as with many an initiative to develop low-income communities, the flows of money continue to rise to the top.

“The CRA’s shortcoming is that it’s just about money coming into the place,” Gregory Jost says. “It doesn’t specify who the money should go to.”

Proposed reforms stir concerns

While community groups beseech regulators for structural changes to the CRA, the baking industry is doing the same.

Both national and community banks have decried the burdensome complexity of the regulations they face, including the CRA. Groups like the Independent Community Bankers of America (ICBA), an association of community-based banks, say their members are crushed under regulatory burdens and urgently need CRA reform. The ICBA has called for a wholesale repeal of section 1071 of the Dodd-Frank Act, which requires banks to disclose demographic data about their small business loans in order to detect discrimination in lending.

The common argument is that small banks have a raw deal and cannot afford to compete with megabanks while also meeting regulations.

But even as banks clamor for relief from the burden they say they are struggling with, they somehow just keep on getting richer, according to Georgetown Law professor and financial regulation scholar Adam Levitin.

“Community banks and credit union trade associations often point to consolidation in their sectors as evidence that their industries are in trouble (for which the solution is invariably regulatory relief of some sort),” Levitin told the Senate Banking Committee in 2017. But community banks already do get a pass on many a consumer finance regulation that their larger competitors are subject to, he said. “Overregulation is not the problem facing community banks…The percentage of profitable community banks at the end of the first quarter of 2017 was the highest it has been in the last twenty years.”

From 2010 to 2017, the average community bank returned a 225 percent pre-tax profit to shareholders. Mega-banks (a Goldman Sachs or JP Morgan, for example) returned to shareholders, on average, 320 percent. That means a $100 investment in a community bank in 2010 would have returned $325 in 2017 before taxes; the same investment in a mega-bank would have returned $420.

“Even as American families are struggling, the banking industry is doing the best it has in years. In such circumstances it takes a certain brazenness to push deregulatory proposals that have nothing to do with fostering economic growth or equitable distribution of growth, only about improving banks’ bottom line,” Levitin told the Senate Banking Committee.

That reality has not stopped the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) from proposing a deregulatory reform to the CRA. The OCC put out a notice in August 2018 that it was planning to “transform or modernize” the CRA with a focus on, among other things, “clarifying and expanding the types of activities eligible for CRA consideration.” After a flurry of comments from advocates worried the law would be watered down, the OCC issued its finalized proposal in December despite the Federal Reserve not being on board.

The reform community groups most dreaded is what they call “one ratio.” The one ratio would mean the standard for CRA compliance would simply be that banks must invest a flat percentage of their money in low-income neighborhoods—taking to the extreme what critics describe as the regulation’s greatest shortcoming: that it simply requires banks to invest a certain dollar amount in low-income areas without specifying what kinds of investments they could be. The one ratio would certainly lift the real or imagined regulatory burden. “The comptroller has a notion that this would make life easier for bank CEOs,” says Josh Silver of the National Community Reinvestment Corporation.

OCC comptroller Joseph Otting is a former bank CEO himself. While many financial regulators come from the securities industry, his professional history and public statements suggest he has a bone to pick with the CRA. As CEO of OneWest, Otting clashed with CRA enforcement after the bank’s much-criticized history of foreclosures during the financial crisis came back to bite. According to records obtained by the Intercept, Otting orchestrated the posting of hundreds of fake positive public comments on OneWest’s merger with CIT to counteract the community groups that were demanding the merger be nixed under the CRA because of OneWest’s previous activities.

The OCC at the time knew about the fabricated comments and approved the merger anyway, according to the Intercept. But Otting, having become the head of the agency, is now a fox in the henhouse. He has described his experience with the merger as a motivating factor in his push for CRA reform, saying he wanted to prevent community groups from being able to “pole vault in and hold [bankers] hostage.”

The one ratio would certainly take leverage away from community groups. And it would give banks a path to knock out their CRA obligations in the most expedient way possible: make a few big loans to big projects in low-income neighborhoods rather than make hundreds of smaller ones. This could deny low-income homeowners or businesspeople the benefits of CRA funding, Silver says. “If a bank could do a large economic development project like a hotel or a supermarket, it could hurt small business and home loans.”

In a house hearing on January 29, Otting emphatically denied the new proposal used the one ratio as a metric. “There is no one ratio in this proposal. That is a myth—that is inaccurate,” he told the House Financial Services Committee. But the proposal as published in the Federal Register creates a “CRA evaluation measure,” defined as the dollar amount a bank invests in low- and middle- income communities yearly as a percentage of its average deposits per quarter. That’s a leg up for banks in and of itself because they would get to compare their CRA activities for the entire year by the average income they receive in just one quarter of the year. That number is combined with the percentage of a bank’s branches that are located in low-income communities, weighted one hundred times less.

The evaluation measure, plus a retail lending test based on a flat percentage, plus a community development test that is also based on a flat percentage make up the CRA’s new criteria. The way the rating is to be computed heavily emphasizes quantitative measures (and lenient ones at that), even though it is not literally comprised of the one ratio.

The proposal does promise to close some loopholes. For example, it would stop giving CRA credit to mortgage loans to rich people living in low-income census tracts, which would alleviate the potential for the CRA to fuel gentrification. But it has arguably awarded a bounty to the rich on a much larger scale: it makes any investment in an opportunity zone eligible for CRA credit.

“Opportunity zones” are zones designated by state governors and the Treasury Department as in need of investment under a 2017 bipartisan tax incentive. Most zones are in urban areas. In New York City, some of the city’s poorer neighborhoods like Brownsville are opportunity zones, but so are affluent and developed areas like Brooklyn Navy Yard. Opportunity zones have been described as a “jackpot” for developers and a “gentrification subsidy.”

Providing CRA credit for any and all opportunity zone investment is a further incentive for speculative investment, Silver said. “We don’t want credit for luxury condos in opportunity zones in CRA exams.”

Unusually, the big three regulators are divided on the proposal, with the Federal Reserve sitting this one out. Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard outlined her own vision for the CRA in a speech on January 8th in which she cautioned against adopting “a uniform comprehensive ratio” on the grounds that it “would not reflect local conditions.” She also endorsed evaluating banks of different sizes differently, proposing a special test for the biggest banks to evaluate their community impact.

Otting declined to take any proposal from the Federal Reserve into account, telling reporters, “There are limited ways the Fed could catch up with us.” The comment period was to close on March 9, with Otting declining requests from Democratic lawmakers to extend it, but he reversed himself to extend the deadline to April 8. The National Housing Conference, an advocacy group, viewed it as a positive gesture. “If the OCC and FDIC really want to improve CRA without gutting it,” said NHC President David Dworkin, “extending the comment period is an important first step.”

Hope for deeper changes

While the OCC has extended the deadline to allow for more comments, the fact remains the agency will set the tone for CRA enforcement for the foreseeable future. But advocates for other kinds of reforms to the law are continuing their work. Even those who fear what the OCC might do under the guise of modernization think the CRA does need to be modernized. For one thing, non-bank lenders (like Quicken Loans) or financial technology companies are not subject to the CRA at all, a loophole that could be easily closed — but the current proposal does not address them.

Amending the CRA’s enforcement metrics is another central concern: the federal enforcement guidelines that have been in place for years take investments into account without assessing their community impact. According to Georges Clement, a data analyst at Just Fix NYC who participated in creating the Worst Evictors list, the fact that regulators and some banks are starting to use advocate-created data analysis to get a fuller picture is a harbinger of what positive CRA reform could look like.

Some banks are using the database whoownswhat.justfix.nyc, the public advocate’s Worst Landlords list and UNHP’s Building Indicator Project to vet their investments in buildings, Clement said. As part of their due diligence process in issuing loans, these banks are referencing data to flag the worst landlords and the most poorly maintained buildings — something that might potentially deny funds to landlords like Wischerth of Parkash, assuming all banks get on board. Clement said, “This type of work is really critical to showing the type of enforcement that can happen in terms of quality of investments.”

Perhaps the most fundamental reform would be to make the CRA race-conscious. While it was passed as a response to a racist policy, the Act itself is colorblind. A proposal to track the race and gender of borrowers and assess the racial and gendered impact of a bank’s lending patterns was rejected in 1999 during Bill Clinton’s updating of the legislation.

Bed-Stuy City Councilman Robert Cornegy, whose district has historically been a hot spot of black homeownership — despite the best efforts of mainstream financial institutions — argues that because black homeownership was what redlining wanted to prevent, it should also be what the CRA aims to promote.

In a speech in September 2018 at a conference on the aftermath of the financial crisis, Cornegy voiced a demand that banks be evaluated based on racial impact assessments of their lending. “How are you building wealth for communities of color? Because there’s a history of stripping wealth from communities of color,” Cornegy said.

“There are conscious decisions that drive who gets the spoils of this great country.”

One thought on “Hopes for Improving Anti-Redlining Law Take a Backseat to Saving It”

Excellent piece. Still, it conflates gentrification with racism. It should not. Banking institutions lending through the regulatory framework established by the CRA aren’t color blind because mega banks lending to large landlords or developers in Op Zones or previously redlined communities are predominantly – NOT – people of color. It just uses the colorblind framework as a shield for racism. Gentrification is its goal, not an effect.